Some of the things I am about to

say may seem obvious. However, I feel

justified as this is a “progress blog” and therefore stating some obvious

things seems appropriate. Research is

the foundation for creating new knowledge.

The investigator must collect what is known and lay that out as the

foundation for building the new awareness and understanding. Historians begin in the past and for us this

is exciting, as recounted in my previous blog.

This journey is a bit different as I am particularly conscious about

laying the groundwork for a Digital Humanities project. I regularly ask the question; how does this

foundation need to be different?

Historians have, as part of the

craft, documented carefully and added to the preservation of historical

records. The citation processes that

terrorize every first year college student are an artifact from the methods of

historians and archivists to mark their trail of research. Change is evidenced in language. Whereas I

have ‘kept track of and documented my sources’, now I am creating metadata,

which includes categories and references not conceived when the trail was

formatted on paper instead of in bits, bites and digital files. “Tagging” has a whole new meaning then in my

teenage years ‘tagging’ artifacts at the local historical society. My research plan has expanded systematically

and strategically to include consideration of how my “data” should be preserved

to provide usefulness and accessibility for projects that may build from mine.

So, after the initial deep dive

into reviewing what is already written about Cleveland’s women, what is the

current status of the foundation? I

received a startling reminder of why this project was initiated in the first

place; where are the women in healthcare?

I had direct confrontation with the question posed by Diana Wendt of the

Smithsonian Division of Medicine and Science; what if there is nothing

there? The “recorded history” of women

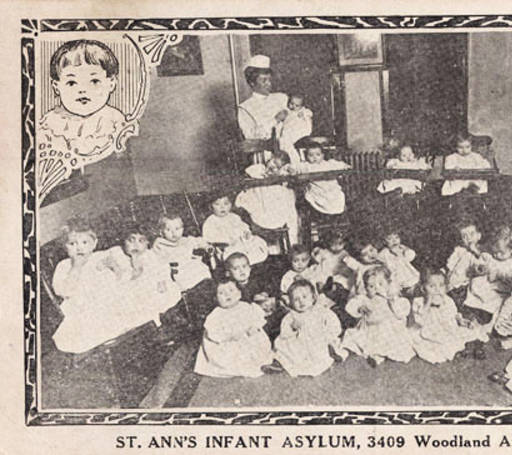

and healthcare in Cleveland is practically non-existent. There are scant ‘pictures on the walls’ of

women in healthcare institutions and in the histories and accounts there are

few names listed. My original heartfelt

response to Ms. Wendt was, “even the absence of information is

interesting.” Fortunately, she agreed.

Now in the face of this glaring absence, the job becomes: to define the size

and nature of the absence, make the history interesting….and digital.

The historian’s task is finding and

interpreting, ‘combing the archives, seeking out new resources; being a

“detective”.[1]

Lendol Calder has reframed this process as “Uncoverage” and advocated inserting

“the work” of historians into history instruction.[2] While women’s history has had to argue that

examination of half the population is truly worthwhile. Sam Wineburg analyzes the significance of

uncovering this different view in his analysis of Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s A

Midwife’s Tale claiming,

“It is in the very dailiness, the exhaustive,

repetitious dailiness, that the real power of Martha Ballard’s book lies… acts

of statecraft (but now) encompasses everyday acts of childbirth, the daily

routines of ordinary people trying to make ends meet.” [3]

To fully understand the human experience; the whole of human

experience must be understood. As a

historian, I need to ask the questions that will reveal the gap of knowledge in

the record and when “telling the story”, convey the significance of the missing

information.

The questions

begin. “Why is there nothing there?”

Just asking the question draws attention away from the existent cultural

script of the “history of healthcare.”

In an of itself the ‘social history of medicine’ is a change, from the

“history of medicine” which only focused on doctors, wrought by the work of

Charles E. Rosenberg, Rosemary Stevens and others. As we investigate, we will find answers. In Martha Ballard’s Diary which recorded, “the long autumns spent winding quills,

pickling meat, and sorting cabbages”, we can see the time-consuming tasks of

women’s lives. Midwifery was Ballard’s source

of income, but would it have been conceived of as “healthcare”? The tasks of women’s lives varied greatly

from men’s. One story observed by Wineman, is

the evolution of the medical profession in which women’s roles and intellect

were subordinated in which he recounted that 20 years after the first medical

course, “a Harvard professor (who) stated, ‘We cannot instruct women as we do

men in the science of medicine’.”[4]

This investigation will

not only create a digital footprint in this area, it will utilize and build

from other digital projects. For

example, The Recipes Project https://recipes.hypotheses.org/category/digital-history in

accumulating and transcribing recipes from 17th century has

discovered a wealth of home remedies and practices previously not viewed as

“innovations in healthcare”. Social and

professional customs and initiatives must also be interpreted in a different

light. Elizabeth Hampton Robb came to

Cleveland as the new wife of a newly hired Western Reserve University

professor/obstetrician. At Johns

Hopkins, Robb was Superintendent of the Nurses Training School. Even in her new non-recognized and non-professional

status, Robb wrote textbooks for nursing, sat on the Board at Lakeside Hospital

and created change in standards and

healthcare practice. More questions are

raised, what impact has women’s acceptance of the social role of ‘Adam’s Rib’,

had on making and sustaining their invisibility in history?

New questions, new formats, new knowledge; the building continues….

[1]

Winks, Robin. Historian as Detective. Harper

& Row, Publishers; 1st edition, 1969.

[2]

Calder, Lendol. “Uncoverage: Toward a

Signature Pedagogy for the Historical Survey”.

The Journal of American History. V. 92, no. 4. (Mar. 2006), Pp. 1358-1370.

[3] Ulrich,

Laurel Thatcher. A Midwife’s Tale: The

Life of Martha Ballard, based on her Diary, 1785-1812. Univ of Virginia,

Knopf, 1990. In Wineburg, Sam,

“Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts.” The Phi Delta Kappan, V. 80,

No. 7. (Mar. 1999), p. 488-99.

[4]

Ibid.